INFLUENCES, PART 5

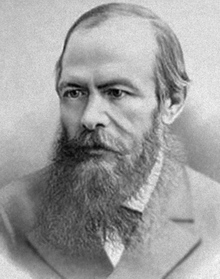

DOSTOEVSKY

Fyodor

Dostoevsky (1821-1881) is one of the most revered of the Russian masters, known

for such works as Notes from the

Underground, The Brothers Karamazov,

Crime and Punishment, and

The Idiot.

As it seems to me, before Dostoevsky I had read mainly stories of action,

ideas, and characters whose motivations and thoughts weighed less than a ton.

Dostoevsky stunned me with the openness and depth with which he dealt

with the minds of human beings,

peering into their complex, often confused workings with an honesty and insight

that was unbelievable: at times disturbing and at other times reassuring (at

least one other man who has lived has had

that thought!) It was another

vision of life which he offered to us through his works, as different from what

we were used to seeing as was our first view of cells under a microscope, or

stars through a spectroscope.

You mean, all that is going on inside of

us??? I guess you could say

that Dostoevsky let me into the house of human

thinking, while before I had been

satisfied standing up on a ladder and looking in through the windows.

He taught me that everything I needed to know about others could also be

found inside of me, if I did not shy away from it and pretend it wasn't there.

He made me aware of things I had carried around and seen but ignored, and

could use as a writer. He inspired

me to make my writer's skin thinner so that I could feel more, register more, so

that a piece of dust could dent me like a comet; he made me perk up my writer's

ears, so that I could hear the dragging feet of a smile, the trace of jealousy

in praise, the sound of a whirlpool in something outwardly clear and stable.

In no way does The March of the

Eccentrics resemble anything penned by Dostoevsky; and yet the expansion in

my soul that occurred as a result of encountering his works has been brought to

bear on my novel, no doubt influencing my psychological treatment of my

characters and filling the story with multidimensional human beings who are a

far cry from the merely functional agents of action so common in our popular

culture today.

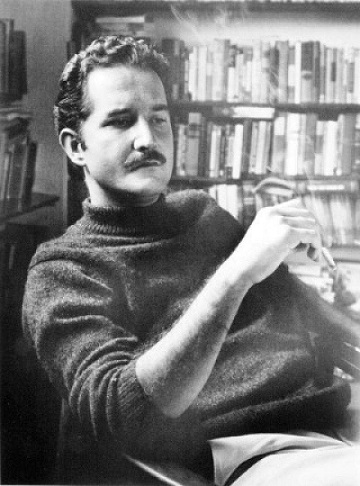

CARLOS FUENTES

Carlos

Fuentes (1928 - 2012), a Mexican literary titan, was one of the great heroes of

the Latin American literary boom in the second half of the 20th century, which

also featured Colombia's Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Peru's Mario Vargas Llosa,

Argentina's Julio Cortazar, and may also be considered to have included Pablo

Neruda (Chile), Octavio Paz (Mexico), Miguel Angel Asturias (Guatemala) and

Jorge Luis Borges (Argentina).

Fuentes is known for such works as La

muerte de Artemio Cruz (The Death of Artemio Cruz),

La region mas transparente (Where the

Air is Clear), Cristobal nonato

(Christopher Unborn), and Gringo viejo

(The Old Gringo). My first

experience was with La region mas

transparente, a novel which branded me with its passion and intelligence,

with the powerful way Fuentes' words came together which you could tell were

driven from his heart. Sometimes,

writers put together excellent sentences that are like glittering jewels

constructed by the mind on a verbal plane, and you are impressed with their

luster, and tell yourself, 'What a good writer.'

At other times, the mind sees things, and gives them to the heart without

taking anything away from the raw sight, leaving the heart filled with feelings

and ready to explode like a volcano. What does it do, then, this overwhelmed

heart, shaking with its muteness?

It seeks words, it demands words, not

as a replacement of itself, but as an expression of itself; it conjures up

language, creates words out of nothing: fiery words, burning words, words that

will not rest till they are felt, words that do not have the luxury of being cut

like diamonds but are born like pumice stones flying out of an inferno.

When you see that kind of writing, you do not say, 'What a good writer,'

you say, 'Lead me to the new world, lead me to love, lead me to life!'

You do not have a decoration in the corner of your room, but an old house

whose walls have been blown down, and a new house that must be built in its

place. And that is Carlos Fuentes:

a writer whose vast intellect did not put out his fire.

The combination of reading Carlos Fuentes and living in Mexico for a year

changed me deeply. I felt the

history and culture of Mexico, the struggle for justice (sometimes involving my

own land in an unflattering way), the pain and the bright sky, the colors and

the secrets, the red blood and the beating heart (you could hear the heartbeats

and feel the thirst on the pages of Fuentes' books), the ancient cities and the

modern smokestacks spewing out forgetfulness and eternal memories, the numbing

indifference in the thin air and the still-standing dreams which have not lost

their voice. All of this has found

a way into The March of the Eccentrics,

in the rivalry between Graciela Sanchez (the populist) and Esmeralda Posada (the

aristocrat), in the setting (Mexico becomes one of the focal points in the

struggle which will determine the future of the planet), and in the

consideration of revolutions, corruption, hope and fear throughout...

I would be an ungrateful man to present this book without first giving my

deepest thanks to Carlos Fuentes, and to the Mexican people who I passed among

for one unforgettable year of my life.

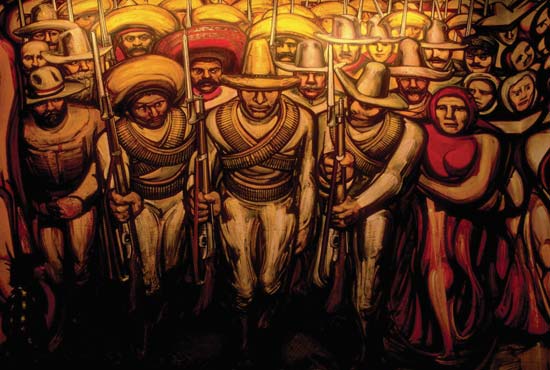

SIQUEIROS

David

Alfaro Siqueiros (1896-1974) is another part of my Mexican influence, a renowned

painter/muralist and peer of Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente Orozco in the visual

projection of the Mexican Revolution of 1910 (and thereafter) into the heart of

a society attempting to reconstruct an authentic and fruitful identity, after

years of being trained to despise its true nature and origins by iron-handed,

European- and American-worshipping rulers.

Certainly a man of many flaws (Siqueiros was a Stalinist who had

participated in an assassination attempt of Leon Trotsky), the vibrancy and

effect of his artistic work could not be denied.

(Thank God, he wielded the paintbrush more expertly than the machine

gun.) I will never forget my visit

to the 'Chapultepec Castle' in the 1970s, and the room on whose walls Siqueiros'

masterpiece "Del Porfirismo a la revolucion" was installed - a heavily

politicized (you could say 'agitprop') form of art depicting the path of Mexico

from the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz (1884-1911) through the revolution which

unseated him. But the amazing thing about this work is that its heavy political

agenda does not undermine it as a work of art, but actually contributes to it.

Here is a piece of art with a clear and unapologetic political message,

stating, with its unashamed colors and boldness that it is not wrong to loudly

and clearly denounce injustice, and that the protest does not have to made

subtly, or obliquely, but can just be put out there like a shout, a shout in

colors: colors of fury and hurt,

colors of revenge and redemption, colors of the human knowledge of right coming

down like an avalanche upon those who have ignored it from the beginning of

time. When you feel that strongly,

overstating is not a sin: what you

do will come out beautiful and it will move people.

That is what I learned from Siqueiros, and what I got from him:

that, and the idea that writing can sometimes be like a painting, vivid

and direct, with words that do not hide, but radiate colors and spread them

through the world.

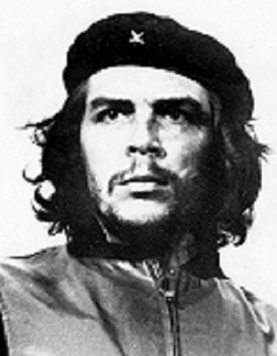

CHE

GUEVARA

And then we come to Che Guevara (1928-1967), the Argentine-born revolutionary for whom writing was too slow and tame a form of affecting the world (although he was also an excellent writer). Today he is most known as a charismatic, striking face on a t-shirt which is cool to wear, but before that, he was the medical doctor from a bourgeois family who worked with lepers and dreamt of curing allergies, before going on to the next level of 'making a difference', which was to become a revolutionary. On his famous 'motorcycle journey' through Latin America, he had seen the rampant poverty firsthand, the gap between rich and poor, the struggle of peasants, miners, and working people to make a go of it - later, in Guatemala, he was an eyewitness to the military coup which overthrew the democratically-elected reform-oriented government of Jacobo Arbenz which was trying to better the lives of such people: a coup which was engineered and backed by the US government (fearing leftist inroads in Central America) and partially instigated by the United Fruit Company in order to protect its vast landholdings from the dangers of agrarian reform. Although many have criticized Che Guevara for his Communist beliefs and embrace of violence as a means of forcing change, President Kennedy himself once stated (in reference to Latin America): "Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable." Che, stung by the lesson of Guatemala, which seemed to indicate to him that the peaceful path to progress was closed, joined Fidel Castro's guerrilla band in 1956 and played a major part in the triumph of the Cuban Revolution in 1959. Subsequently, he fought on the side of revolutionaries in Africa, and led a revolutionary front in Bolivia (hoping to spark an uprising which would engulf the entire South American continent); there he was killed, in 1967... During the 1960s in the US, Che, drawing attention for his charisma and oppositional attitude (the 60s was very much about opposing the status quo), became an icon of radical thinkers. Wrapped in a romantic aura - lifted to a pedestal by his undeniable integrity, courage, and altruism - and finally beatified by his quasi-religious martyrdom in Bolivia - Che became a larger-than-life symbol of the quest for justice in its most daring, uncompromising and strident form. He was like a God at whose altar people worshipped - posters (sporting the above photograph) went up on the walls of many thousands, some merely admiring him, others wishing to become like him. Che had a big effect on me for the same reason he had a big effect on so many others of my generation: whether you agreed with his methods and philosophy, or not, he was genuine: a man who lived according to his beliefs, a man who was true to the principles which he had, a man who forsook a life of comfort to throw his lot in with the poor, the hungry, the needy, and the desperate of the earth, a man who may have mixed company with cynics and users, but was not one himself. There was a purity there (as much as a real flesh-and-blood man can embody, for anyone who lives is stained), and we were inspired by that purity. In The March of the Eccentrics, Che Guevara's influence is present in many ways. There are guerrillas and revolutions, and large swaths of social injustice blockaded from peaceful resolution by dictatorships, which justify those revolutions; there is a young New York City writer (Mick) who is an ardent devotee of the Che cult; and there is the New York City 'foco', a kind of 'insurrectional center' of culture-rebels bent on spreading a lifestyle revolution throughout America, their ideas of change loosely based on Che's doctrine of the 'revolutionary foco.' The difference is, they do not seek to use bullets, only their love of life and their social inventiveness... (For another story which deals even more directly with the legacy and role of Che Guevara in environments of intense oppression, see my novel "A Superstition of the Poor" at http://www.rainsnow.org/cshf_superstition_of_poor.htm .)

BLOG LAUNCH PAGE