Hiroshima Speaking Through Sadako

Somehow,

this has turned out to be my 'Japan Week.'

Japan

and its people play a major part in my novel,

The March of the Eccentrics.

There is the fabulously effective Ishimatsu Corporation, which becomes

linked to the international Eccentrics movement of Julius Herman Abu as the

industrial component of his inventive genius; the master scientist's blueprints,

designs, or mere ideas are made concrete by the manufacturing brilliance of the

Ishimatsu Company, which is not only a business powerhouse but also a

sociological wonder. Then, there is

the aged World War 2 veteran, the loyal and resourceful Takaji Umezu, recently

extracted from the jungles of the Philippines after he is finally convinced that

the war is over and that his duty to the Emperor has been honorably fulfilled;

while, on the more modern side, we have Yuki Onomatsu, the wild Japanese

teenager who dyes her hair orange, dresses in the most outlandish of ways, and

does her very best to shatter every convention she can think of, at the same

time that she homes in on Freddy Wells as her idol/love-interest/and connecting

point with the Eccentrics movement.

Early on, a strong bond is formed between the Japanese and the Eccentrics, an

odd pairing at first if you think of Japan as an acutely collective and

conformist society, but a natural coupling if you, instead, think of Japan as a

stronghold of innovation, adaptability,

sensitivity, and high aestheticism.

The uniqueness and striking beauty of the culture at its best, as well as

its ability to courageously face challenges and shifts in global paradigms, make

the match near perfect. Thus, in The

March of the Eccentrics, we have amazing deep-earth burrowing machines (made

in Japan), powerful robot-like shells for human warriors known as Pedipulators

(made in Japan), industrial robots and automatic assembly plants (made in

Japan), formidable MODSAMs ("modern samurai", made in Japan by mothers, fathers

and sensei!), motivational courtesans (made in Japan, the old-fashioned way),

ganguro girls (m.i.J.), sumo

wrestlers (m.i.J.), allusions to Japanese literature (m.i.J.), haiku and tanka

poems (made in Japan, or by Japanese), and Zen Buddhism

(no-mind no-made in no-Japan).

Contact points are everywhere, and it is no surprise: the level of

engagement reflects my own fascination with Japanese culture from as far back as

I can remember...

Which is

probably how this week, for me, ended up being 'Japan Week.'

(Yet another Japan Week!)

*****

This

week's Japan Week, materializing outside of the pages of my novel in a place

known as 'the real world', began on Sunday, April 26 at Brooklyn, New York's

Botanic Garden, where an event known as the Sakura Matsuri, or Cherry Festival,

was being held. Although events and

related activities were located at various points throughout the Botanic Garden,

the center of the action was at the Cherry Esplanade where a large stage had

been set up. The cherry trees,

themselves, were not about to be rushed by the presence of the Festival, and

were, for the most part, still keeping their blossoms under wraps, small and

hidden as pre-bloom. The result was

slightly austere, parallel lines of somewhat bleak trees which had not yet

recovered their full personality after a hard winter; but the dangling little

pseudo-buds gave signs of hope, they were like the flash at the end of a match

before you get the flame to ignite a torch.

And they were a valuable reminder to all in attendance that glory comes

from humble beginnings, that men do not rule nature but must abide by it, and

that patience and faith are irreplaceable virtues...

On the other hand, I am not sure if the trees were trying to teach us the

power of waiting, or if they were merely holding back their blossoms for a week

so that the people in attendance could, themselves, become the vibrant life and

color of the esplanade: families

with tired children who couldn't see a thing except legs; families with

rambunctious, playful children running wildly around; families picnicking and

exuding closeness and relief (the relief of finally having quality time

together); children sitting on the loving shoulders of parents, not yet worn out

by the spectacle taking place on the stage; radiant couples in love, or just

nerdy buddies chilling; a heavy proportion of Japanese faces, as expected,

gathering to enjoy echoes of their culture in the Big Apple, but people from all

cultures and races coming to partake; cosplay kids inspired by manga drifting

about like exotic stars from sci-fi or pirate flicks; some beautiful young

ladies in traditional kimonos...

human cherry blossoms... Maybe the trees were merely gracious hosts, standing

back to let those who came to admire them admire themselves.

One of

my favorite people-watching moments at the Esplanade, as I waited for the shows

on the main stage to begin, was the boisterous little boy who climbed high up a

tree and found it harder to get back down.

In the manner of the ancient Japanese, who seemed to compose poems on the

spot on almost every occasion - full moon, snowfall, cherry blossoming, goose

honking, man's hat getting blown off by the wind - I made up one of my own (why

just say, "Hey, kid, what the hell are you doing up there?" when you can compose

a haiku?). Here it is:

Cherry-tree-looking:

Not

enough for the small boy.

Now:

stuck in a branch!

Not an

admonishment, however; more of a celebration of the glories and risks, which

lead back to the glories, of becoming truly involved in something, of fully

plunging into it (like 'the river of Zen'), of total immersion in life - no, no

criticism here, just solidarity: I

got your back, kid! (And yes, he

did get back down safely. And I did

not have to write the follow-up poem:

Bloody kid on ground./I stood by

doing nothing./But what a poem!)

Then,

just as it seemed that watching the watchers would swallow me up, the stage

finally got my attention - and how!

This wild group of Taiko Drummer girls known as Cobu began to perform.

Colorfully dressed, vivacious, agile and seemingly beyond exhaustion,

they began pounding on a series of large drums, mainly with sticks though

sometimes with hands, at the same time that they danced at their drums,

frequently changing positions with each other without losing a beat; there was

something fiercely martial about their movements, which hovered between joyful

flirtations with rhythm, and mock battles in which their drumsticks were wielded

as weapons; during one number, they

beat off another woman who whirled among them with a staff, driving her away by

hitting her staff with their sticks, which contributed to the masterful

percussive chorus. The beats,

combined with these beautiful young women hurling themselves around like spirits

of nature, put me into a deep trance, and all kinds of feelings and thoughts

broke out of the inner vaults I had been keeping them locked in.

I was flooded by love, by memory, by a reconnection with the power of

nature (which these animated Shinto fairies seemed to be personifying), I was

flooded by dreams, by life, by transience, by the intensity that compensates for

transience, by old hurts and new hope, by feelings of insufficiency, and

recognitions of might. I was lifted

out of something like a pit by the frothing energy, and ended up atop something

very much like a peak. Then, next

thing I knew, I was clapping my hands as the girls took their final bows, and

waking up again to where I was - except that I wasn't there anymore!

-- Thanks, Cobu!

Following Cobu, and my wanderings about the Osborne Garden and the cosplay and

manga tents before returning to the Esplanade, was an act called 'Dancejapan

with Sachiyo Ito': Elegant and colorful Kabuki Buyo dance.'

From this, I recall four mysterious women with faces painted white,

wearing traditional kimonos as they danced together gracefully and cryptically

on the stage. Something about their

faces - those stylized smiles, not giving away too much - 'what are they

thinking?' - reminded me of the Mona Lisa, except that the Mona Lisa seemed far

more harmless. I could imagine

these Kabuki women stabbing me in my sleep or poisoning my tea, and yet there

was something about them so alluring that the risk would be well worth it.

They made me think of Circe, the sorceress from ancient Greek mythology

who turned wayward sailors into pigs, and I told myself, 'Yes, these could be

Japanese Circes.' Somehow, they

seemed to possess keys to something I needed, and I wondered if I could get them

on my side. Strange - I think they

were only trying to be elegant and enticing, but for me they became clouds,

immeasurably graceful and perilously obscure, hiding, inside them, fire, life,

death, treasure... I couldn't be

sure which.

And

then, it was on to an entertainment troupe known as 'Samurai Sword Soul', which

at the beginning disappointed me. I

had thought there was going to be something fearsome and spectacular, here,

featuring the likes of Miyamoto Musashi and Sasaki Kojiro, with genuine kendo

matches, and/or world-class kata.

Instead, it rapidly became apparent that the troupe was putting on a comic play

utilizing many martial arts stereotypes and stock expectations, and that the

performance was geared towards kids.

But my disappointment did not last long.

After only a little while I discovered that I was far more juvenile than

I had originally thought! I got

into the play, enjoyed the groove of the kids around me enjoying it, and finally

began to enjoy it even without their help!

I especially liked the girl ninja who was great fun, and as the show did

hit a poignant moment in the midst of the outright comedy and the campy drama, I

even started to tear up - oh no, how bad was that????

Get a grip on yourself, J!!!!!

And

those were the highlights of my Sakura Matsuri experience, the first installment

of my recent Japan Week...

Cobu In Action.

*****

The

second installment occurred when I got a ticket to see "Kumiko, the Treasure

Hunter", a recent film starring Rinko Kikuchi and inspired by the tragic life of

Japanese office worker Takako Konishi, or more accurately, by the urban legend

which developed around her death (may she rest in peace).

In this American/Japanese movie, Rinko Kikuchi plays a Japanese office

worker by the name of Kumiko, whose life seems to be hitting a dead-end.

In Japan, the OL (or office lady) is a class of worker, usually recruited

to work for a company at a very young age, who is expected to brighten up the

office environment with her youth while doing clerical or service tasks that

have no future. She is expected to

eventually find a husband who will take care of her as she tends his home and

their children, and to leave the world of work before she has reached the age of

30.

It is

clear as the movie progresses that Kumiko is disgruntled with her job, harried

by her mother, dogged by her age (which is approaching the end of the Office

Lady cycle), and hemmed in by social expectations and limitations.

Her situation is becoming increasingly bleak. She is clearly depressed,

becoming increasingly antisocial and isolated, and apparently, at least to my

eye from the way Rinko K. plays her, mentally ill.

In the midst of the gathering gloom of her life and its closing

prospects, Kumiko comes upon a VHS copy of the American movie 'Fargo', and

becomes convinced that the case full of cash buried in a field of snow along a

highway by one of the characters in the movie, is real.

The opening credits of the movie 'Fargo' state:

"THIS IS A TRUE STORY. The

events depicted in this movie took place in Minnesota in 1987.

At the request of the survivors, the names have been changed.

Out of respect for the dead, the rest has been told exactly as it

occurred." Although, it turns out,

this claim was completely incorrect and the movie was utterly fictional,

incorporating a variety of crimes committed in other locations into its own

imaginary trajectory, Kumiko, reading Japanese subtitles for this claim on her

own poor-quality tape of 'Fargo', becomes convinced that the treasure is real;

and in light of her own shrinking world, she clutches at it as her only hope for

remedying her situation - for gaining independence, freedom, a chance to break

out of the system that is poised to strangle her...

Kumiko's

preparation for zeroing in on the treasure is a combination of

methodical/detail-oriented, and wildly imaginative/incompetent.

She watches the movie over and over again, taking notes, drawing a map of

a fence-line along the snowy field where the treasure is buried and carefully

calculating distances between posts; then tries to steal an atlas from a library

in Tokyo as if its map of Minnesota and North Dakota could truly constitute a

worthy field guide. She is able to

get a ticket and arrange the flight to Minneapolis as her starting point, but

comes woefully unprepared in terms of winter apparel, and language skills (she

can't speak English, and yet still believes she will be able to maneuver through

this unknown land without it.) The

whole concept of the treasure hunt is not thought through at all, there are

enormous gaps in Kumiko's reasoning and appraisal of the situation; but what is

not lacking is belief - absolute belief - no one can tell her otherwise - that

the treasure is real; and desperation - absolute desperation transformed into

unshakable determination. This is

all or nothing. Without this

fantasy, she has nothing, and she is therefore committed to letting nothing

disown her of it. The world has

made truth unlivable, so this dream has become her air; and as her mother

deserts her with her lack of comprehension, so this dream also becomes Kumiko's

only home.

To be

honest, I had a lot of problems with the movie.

It has been described by some as a comedy/drama, or black comedy, but I

was unable to laugh at any of Kumiko's absurd errors or exaggerated behaviors,

because given the state of her mental illness and the pain from which her

delusions sprang, that would have felt cruel.

There were also some potentially funny moments depicting the cultural

ingenuousness of Americans, so imprisoned by stereotypes and inexperienced with

other cultures except on a superficial level, but these, too, provided only

surface ripples of amusement on the dark waters of a gathering tragedy.

Meanwhile, it was hard for me to identify strongly with Kumiko and to

feel sympathy for her, because she was portrayed in such a shut-down way.

Most likely, this was a masterful impression of someone in the grip of

severe depression, but without strong and emotive signs of life within that grim

and broken mind, it was hard to connect to her - we had never seen Kumiko

before, when she had had joy or hope; even in the pursuit of the treasure, she

seemed robotic, even catatonic.

Deprived of a vision of her spirit's downfall, before so much of her was emptied

out and crushed, I could not get my arms around her tragedy, it was as if the

movie had begun with her being already dead.

There was no one to mourn, it was over before it began.

But the

dark emotional tones of the movie which kept me as an outsider for much of it,

were offset by the brilliant cinematography; that is where the color and life

were. Kumiko's bright red 'hoodie'

was perfect for the landscapes she traversed, for the snowy wide skies and

highways; and then, the way she tore a hole in a hotel comforter/blanket to

convert it into a poncho (a trick I replicate with bags in inclement weather),

opened the door for yet another masterpiece of color.

That brilliantly patterned, bright blanket, meant to help her endure the

bitter northern temperatures she had not come prepared for, seemed to become an

amazing kimono, highlighting her strangeness in a landscape she did not know or

belong in, at the same time as it embellished her with a kind of mysterious

magnificence, converting her into an almost magical or royal figure.

She was then like a queen without a kingdom, searching for her throne,

and the blame for her peculiarity seemed to shift to the world for not giving

her her rightful place.

Nonetheless, I continued to remain with my heart outside of the movie until the

very end, when a 'Snows of Kilimanjaro' moment took place.

At that moment, the beauty of Kumiko's personality suddenly erupted,

Rinko's face lit up, all the happiness and life and attractiveness of this human

being if she had been properly treated and appreciated and recognized came to

the surface and filled her up, and jumped out of the screen at me.

The sight of her and her great, colorful eccentric garment, her beloved

rabbit Bunzo in her arms, the treasure of life, itself, in her possession, as

she strode across the enormous snowscape to the march-like, upbeat music of

'Yamasuki' - that did bring tears to

my eyes: sorrow and joy mixed in nearly equal portions:

a fair approximation of life. And

I was left to wonder: what is

illusion? Is illusion the dreams we

cherish, that engage our passions, give us hope, and inspire us to fly with all

the boldness and beauty of our souls into the emptiness, or is illusion the

sterile reality a whole world clings to and tries not to fall off of?

In this fairy-tale created from a misunderstanding, we see the power of

living for something that matters, even if it is not 'real' to others.

Most certainly, Kumiko should not be taken as a role model for anyone to

emulate - but neither should this world of stifling conventions and human

coldness (as cold as the winter of Minnesota) be taken as something to

perpetuate. Kumiko, Kumiko... maybe the

treasure you found is the understanding that we need to break through the ice to

make the world anew.

Rinko Kikuchi As Kumiko.

*****

And this

is how I spent my Japan Week!

Uplifted and entranced by the Sakura Matsuri; and wounded by "Kumiko, The

Treasure Hunter", but with my pact with the different, the strange, the

original, and the beautiful people of the earth renewed.

Thank

you, Japan, for enlarging and energizing me yet again.

You do it every time.

April

30, 2015

As I

write these words, the 70th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima approaches.

There are those who still argue on behalf of the use of 'the atomic bomb'

against the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, using one angle

or another to justify the unleashing of the most terrible destructive force ever

created by Man. Whatever credence

one may give to their rationales, when one looks at the brutally indiscriminate

nature of these weapons which made no distinction between arms factories and

homes, or between soldiers and schoolchildren, and which quite possibly

swallowed up (within several months of their detonation) over 150,000 lives in

Hiroshima and 75,000 lives in Nagasaki, one can only come to the conclusion that

the human race, even with its incredibly long track record of cruelty, had, with

these events, finally outdone itself and attained amazing new heights of

barbarism. The paradox is that the

incredible intellectual progress necessary to create an atomic bomb in the first

place had in no way been matched by the development of human compassion or by

the elevation of our moral sensibilities. The heart which had formerly propelled

one man to bash a stone against another's head had not changed, only the means

of enacting violence, which had become more sophisticated, even acquiring the

trappings of divinity as Man began to dabble with the most intimate secrets of

the Universe. Tellingly, the means

of destruction also became more remote:

in a 'history of distancing' first begun as the bow and gun replaced the

knife and spear, then as the artillery piece outshot the rifle, and finally as

the airplane lifted the warrior into the clouds, transforming killing into the

mere act of pushing buttons and pulling levers, the anguished eyes of the dying

receded ever farther from the death-dealer.

At the same time as the magnitude

of destruction in Man's hands grew, his awareness of, and contact with, the

results of his actions faded: a

dangerous combination. Explosions,

clouds of dust and debris rose up from beneath the windows of his speeding

aircraft: it was like artwork, this

creating of patterns and colors and lights with smoke and explosive, this

toppling and crumbling of inanimate things, this redesigning of the earth

without visible faces or blood to constrict the mission.

One old-school pilot (an Italian involved in the assault on Ethiopia)

even compared the landing of a bomb in the middle of a group of horsemen riding

below to a budding rose unfolding; while others reveled to watch bridges

disappear, and the texture of cities cave in, these little bumps and ridges that

once were buildings lose form and remake themselves into shadows of the

emptiness that had gone before ...

The disconnect between those who took lives and those whose lives were taken,

grew, and with that came the ability to destroy Hiroshima and Nagasaki; and if

we do not learn from what happened there, and find a way of shrinking the

disconnect quite soon, even greater disasters will one day come our way,

muscling their way in past our fear of playing with fire (for we do fear these

deadly weapons and their boomeranging possibilities).

In the face of this trend, there is no doubt that we must cease to allow

the range of our weapons, the distance which they allow us to kill at, and the

power with which they envelope and disguise the dead (burying them alive,

swallowing them up, or making them vanish into thin air), any longer hide from

us the reality of what we are doing to others; only if we are aware - truly

aware - of what we are doing, will our humanity have a chance of kicking in.

And only if our humanity kicks in, can we prevent our technology from

falling under the sway of our darker habits and the terrible inertia of a long

history of hurting others to get what we want...

Which

brings us to Sadako Sasaki, the well-known schoolgirl from Hiroshima,

two-years-old at the time of the atomic bombing...

This innocent child who had harmed no one and done no wrong to anyone -

this poor young soul, caught in the crossfire of a terrible war in which cruelty

had run rampant, and anger and racism had risen up in defense of democracy - was

hurled out of a window by the blast of August 6th, 1945, yet miraculously

survived. Some years later,

however, the dark shadow of what had happened to her city came back for her in

the form of leukemia, the result of her childhood exposure to the massive doses

of radiation unleashed by the Hiroshima bomb.

Sadako fought back bravely, but the disease was too powerful, the damage

wrought upon her body from the bomb too severe.

Her last days were spent in a hospital, making origami cranes:

for, according to a popular Japanese legend, whoever made a thousand such

cranes would have a wish granted to them by the divine power.

12-years-old now, Sadako was still far too young to die, and her wish was

sure to have been a simple one - to have a life like the rest of us, with

energy, hope, and the time to make her life into something beautiful or to waste

it on her own terms. Making these

origami cranes, a kind of prayer in action, was no simple matter.

The attention, precision, and number of folds required to make each one

well was impressive (I watched several YouTube tutorials on how to make them and

can definitely say that making paper airplanes, the closest I have ever come to

doing origami, is not in the same league, or even planet.)

While in the hospital, Sadako often ran out of paper for making the

cranes, whereupon she would get up and go around visiting other patients, who

were glad to lend her the wrapping paper from get-well gifts they had received;

her friends, also, would bring her whatever paper they could get their hands on

when they came to visit her.

According to some accounts, Sadako never made it to 1,000 cranes, while

according to others, she did, but without her wish coming true.

Whatever the case, this courageous young girl whose plight and tragic

demise have now struck a chord with millions, gave out on October 25, 1955.

But the spirit of her struggle, and the vision of her shining human light

unjustly put out by the brutality of intellect divorced from love, by the power

men who killed her without knowing her - men who struck without awareness,

destroying a treasure in the darkness (and not just Sadako, but also thousands

like her) - live on, capturing our imaginations and finally giving a face to the

unseen world underneath the bomb sights.

In the end, the cranes which Sadako folded did come to rescue her - if

not from death, from invisibility.

Today, we honor Sadako for inserting her humanness into the vacuum of our

conscience, for shoving aside the mechanical vision of genius which makes

genocide possible and standing in plain sight before our eyes, between us and

the easy way to get what we wish: the easy way of believing that no one else is

real and that there is therefore nothing standing in the way of our most

thoughtless ambitions.

In

The March of the Eccentrics novel,

the young scientific genius Julius H. Abu, especially moved by the history of

Hiroshima, seeks to create a new union of international scientists dedicated to

combating the misapplication of Man's scientific knowledge and technical

abilities, and to transforming the nature of Western civilization, itself, so

that peace may finally reign as human genius is unhitched from human cruelty

(Chapters 8 & 9). His great new social

experiment runs into difficulties, however; and the rest of the novel is filled

with combative episodes. On the

other hand, these episodes should in no way be taken as a paean to war, but,

rather, as metaphorical literary vehicles emphasizing the importance of our

human capacity to struggle, with courage, for fairness and justice on the earth.

And throughout the chronicles of conflict, we increasingly encounter the

burgeoning compassion of Ellen Abu, acting as a counterweight to superficial

dreams of glory or fantasies bred by anger, and seeking at every moment to

humanize a world which has lost its way in the blinding smoke of its ambition...

Ultimately, I see The March of the

Eccentrics as an instrument of peace, calling for a renewal of the earthly

powers of love and hope, the only powers that ever could and yet might save us.

It is a novel written by a man scarred by the memory of an event he knows

only through the testimony of others - the story of a terrible mushroom cloud

uncorked by his own country on a dark, cold-hearted morning, and forever

personified by the innocence of a young girl who could not fly, folding cranes

who could.

May my

novel, somehow and in its own small way, serve the fallen, and further the

promise of the living and the unborn...

July 26, 2015

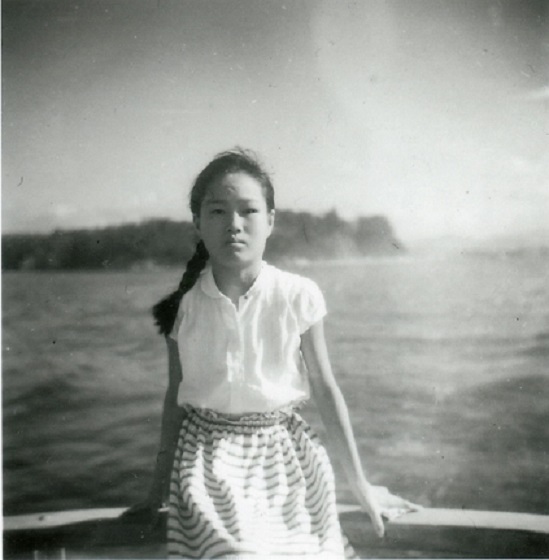

Sadako Sasaki: an embodied plea for peace.

Planet Earth will be at risk until the day each one of us adopts her

as our sister.