The Origins of War in a Technological Society

President Obama's Hiroshima Speech

The

cheetah is one of the fastest animals on the ground.

He can run 70 mph in an amazing but limited burst of speed that few

creatures can elude without putting on some world-class moves.

But if the cheetah fails to bring his prey down quickly, he tires, and

next thing you know he's lying down in the grass with his tongue hanging out,

regretting the one that got away.

The wolf can't come close to the cheetah's velocity, but what he has that the

cheetah does not is an incredible patience and devotion to the hunt that is

imbedded physically into his being in the form of endurance.

If his prey eludes him and runs circles around him at first, even makes

him look like a fool, he doesn't seem to mind; his will is immune to ridicule,

his desire impervious to failure:

he just keeps at it. He will run

for hours through the snow on frozen bleeding feet, hard like iron, unyielding,

not because he does not suffer, but because he senses what is on the other side

of his suffering: what he

lives for, what he

must have.

Some

artists, a very few, are like successful cheetahs - they sprint out of the

cradle, out of some young-man's or young woman's awakening, at a maddening pace

that nothing can resist; they triumph at the outset.

Many

more are like cheetahs who lose the sprint... whose stunning first burst of

speed and self-confident dream of glory is stymied by the elusiveness of the

rare prize in a material world that does not shed a tear for those who are

dissimilar; they run and run... 'why doesn't anyone buy my record, my painting,

my book?' - they keep on running... the world runs faster; they gasp, they pant,

they don't believe - 'no one gets it, they don't see how good this is?'; until

finally, they lie down, exhausted, beaten, along with all the beautiful things

they could have given the world, letting silence cover them over, like moss on a

grave. They put the gray coat on,

get back onto the rush-hour train, and vanish from the creative universe, like a

guitar in a closet, like a manuscript in a trunk.

(Or else they self-immolate, leaping into the abyss of hunger, or drugs

meant to gouge undeniable acts of godhood from their brains.

But the fire kills their gifts just as much as surrender does.)

"Time for a new role model." Keep reading!

Finally,

there are the cheetahs whose love changes them into wolves.

What they could not gain in their first, youthful sprint remains too

precious to be abandoned. They make

the compromises necessary to carry on, to extend their chances, and keep at it,

year after year, their eyes never looking away from the prize.

They hold onto jobs that sustain them and prolong them without letting

the jobs swallow their dream or steal their soul, neither the good jobs nor the

bad ones; they save time and energy like a poor man saves pennies, building them

up into viable amounts; they splice together fragments of inspiration stolen

from the contours of defeat which surround them but do not absorb them, and

begin to construct coherent trajectories of imagination with their long-distance

strides; they hollow out caves for worthy projects in the side of the mountain

of muteness, and blow on the embers of their silenced voice until their thoughts

finally ring out in the world; lost youth

is brought back to life by the power of inextinguishable belief.

These

are the cheetahs mutated by love into wolves; the slowed-down ones, less

glamorous but firmer, less euphoric but more lasting, who keep on going and

going; going past rejection, going past defeat, through the years, through the

snow, through the cold places that hurt the lungs; on and on and on, because

they just can't give up, they just can't live without it.

These are the ones who don't stop learning, the ones who are not crushed

by doubt but fight their way to the other side of it, where they are twice the

size; the ones who watch, who grow; who hunger and don't allow the hunger for

what they love to be satiated by the food of what is asking them to sleep...

These are the wolves, the most real, the most impressive of all the

soul-fighters, the ones who will run till they drop.

The ones who bear the most difficult beauty, the ones entrusted to lift

the world up!

My

creative friends - join us, the wolf people of the arts!

The battered veterans of the new-world-to-be, holding out in the ravaged

cities of Mammon; the still-shining jewels of the semi-wrecked life; the eternal

flame of human creation! Do not

surrender, do not lose hope! It is

never too late, it is never too far.

Do not ever think you were wrong!

Strategize, renew! Remember

the wolf, and find ways to keep on running, to keep on chasing the beauty that

none of us can do without!

('Appendix.' My favorite

inspiration below the ticking clock:

Miguel de Cervantes, who didn't publish Don Quixote until he was 57!

And then there was 'Grandma Moses', who didn't 'break out' till she was

80! -- Wolf howl!!!)

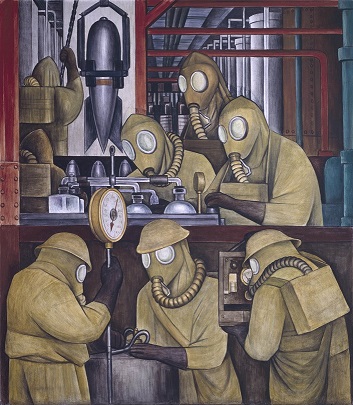

"Manufacture of Poison Gas Bombs" by Diego Rivera (for the Detroit Industry

Mural, 1932), depicting the capture of man's technological genius by his darker

instincts.

Every

once in a while, as one reads and studies and ponders the dilemmas of the human

race, one stumbles upon a book or passage from a book that is especially

enlightening... something that, from within a chorus of expected and unedifying

voices, suddenly breaks through with unmistakable newness, clarity and

believability. It is the difference

between listening to Maria Callas and an elementary school choir; of hearing

cowbells dangling from the necks of cattle, or the mighty, giant bells of a

church tower, ringing over the city.

When I first read Lewis Mumford (1895-1990), an American sociologist,

historian and literary critic of extraordinary breadth and uninhibited opinions,

I encountered one such passage: a

passage about the causes of war, which went far beyond the usual explanations

we had heard till then - the

rationally-driven battles for resources, geographical strong-points, trade

routes, markets and sources of tribute which had propelled empires and nations

to construct competing systems of power destined to engender conflict.

Doubtless influenced by Freud's 'Civilization and its Discontents'

(1930), and inspired by the age-old search for the miracle of peace (which must

begin with a deep understanding of the causes of conflict), Mumford turned out

an amazing passage inspired by the reality of his own day, which was, in turn,

influenced by the horrific experience of World War One, when all the progress of

the Enlightenment (epitomized by Voltaire's merciless condemnation of militarism

and madness in 'Candide') and the supposed love-teachings of Christianity were

trampled underfoot by the savagery of technologically-enhanced nations.

It was as if all the progress had never taken place, or worse yet, had

only been built up to make a bigger crash.

Mumford, attempting to reinterpret the new forms and genesis of wars in

his own lifetime, as his contribution to the understanding that might allow men

of conscience to one day rein in the dark forces of violence, wrote the

following lines (p. 307-311 of Technics and Civilization, 1934).

I post these little-remembered, but important words, for the benefit of

our mutual ascent:

“...In almost all its manifestations, however, war indicates a throwback to an

infantile psychal pattern on the part of people who can no longer stand the

exacting strain of life in groups, with all the necessities for compromise,

give-and-take, live-and-let-live, understanding and sympathy that such life

demands, and with all the complexities of adjustment involved.

They seek by the knife and the gun to unravel the social knot.

But whereas national wars today are essentially collective competitions

in which the battlefield takes the place of the market, the ability of war to

command the loyalty and interests of the entire underlying population rests

partly upon its peculiar psychological reactions:

it provides an outlet and an emotional release.

‘Art degraded, imagination denied,’ as Blake says, ‘war governed the

nations.’

“For war is the supreme drama of a completely mechanized society; and it has an

element of advantage that puts it high above all the other preparatory forms of

mass-sport in which the attitudes of war are mimicked:

war is real, while in all the other mass-sports there is an element of

make-believe: apart from the

excitements of the game and the gains or losses from gambling, it does not

really matter who is victorious. In

war, there is no doubt as to the reality:

success may bring the reward of death just as surely as failure, and it

may bring it to the remotest spectator as well as to the gladiators in the

center of the vast arena of the nations.

“But war, for those actually engaged in combat, likewise brings a release from

the sordid motives of profit-making and self-seeking that govern the prevailing

forms of business enterprise, including sport:

the action has the significance of high drama.

And while warfare is one of the principal sources of mechanism, and its

drill and regimentation are the very pattern of old-style industrial effort, it

provides, far more than the sport-field, the necessary compensations to this

routine. The preparation of the

soldier, the parade, the smartness and polish of the equipment and uniform, the

precise movement of large bodies of men, the blare of bugles, the punctuation of

drums, the rhythm of the march, and then, in actual battle itself, the final

explosion of effort in the bombardment and the charge, lend an esthetic and

moral grandeur to the whole performance.

The death or maiming of the body gives the drama the element of a tragic

sacrifice, like that which underlies so many primitive religious rituals:

the effort is sanctified and intensified by the scale of the holocaust.

For peoples that have lost the values of culture and can no longer

respond with interest or understanding to the symbols of culture, the

abandonment of the whole process and the reversion to crude faiths and

non-rational dogmas, is powerfully abetted by the processes of war.

If no enemy really existed, it would be necessary to create him, in order

to further this development.

“Thus war breaks the tedium of a mechanized society and relieves it from the

pettiness and prudence of its daily efforts, by concentrating to their last

degree both the mechanization of the means of production and the countering

vigor of desperate vital outbursts. War

sanctions the utmost exhibition of the primitive at the same time that it

deifies the mechanical. In modern

war, the raw primitive and the clockwork mechanical are one.

“In view of its end products - the dead, the crippled, the insane, the

devastated regions, the shattered resources, the moral corruption, the

anti-social hates and hoodlumisms - war is the most disastrous outlet for the

repressed impulses of society that has been devised.

“…War, like a neurosis, is the destructive solution of an unbearable tension and

conflict between organic impulses and the code and circumstances that keep one

from satisfying them.

“This destructive union of the mechanized and the savage primitive is the

alternative to a mature, humanized culture capable of directing the machine to

the enhancement of communal and personal life.

If our life were an organic whole this split and this perversion would

not be possible, for the order we have embodied in machines would be more

completely exemplified in our personal life, and the primitive impulses, which

we have diverted or repressed by excessive preoccupation with mechanical

devices, would have natural outlets in their appropriate cultural forms.

Until we begin to achieve this culture however, war will probably remain

the constant shadow of the machine:

the wars of national armies, the wars of gangs, the wars of classes:

beneath all, the incessant preparation by drill and propaganda towards

these wars. A society that has lost

its life values will tend to make a religion of death and build up a cult around

its worship - a religion not less grateful because it satisfies the mounting

number of paranoiacs and sadists such a disrupted society necessarily produces.”

It was reading this passage, and later Freud, which sparked the intuition in my

own soul that the search for world peace must bring us deep within to a new

understanding of ourselves; and that only by re-engineering our culture to be

compatible with our true nature, and by generating new avenues of expression and

living that will increase our commitment to life, new venues for the

construction and defense of our self-esteem (that do not involve extremism), and

new outlets for the safe venting of our remaining frustrations which otherwise

might be 'captured' and manipulated towards war by would-be riders of our

discontent, can we steer a new and stable course around the inevitable obstacles

that will confront us in the near future and the far future.

Psychologically defused and de-energized, those obstacles will not be

hard to overcome; it is only our own internal mess, fostered by an unhealthy and

emotionally inefficient culture, which makes those obstacles 'gigantic' and

'insurmountable.' Our wounds

add daunting layers to them; just as our healing will reveal the power to

simplify the most labyrinthine of political enigmas.

Once we truly get a grip on ourselves and no longer feel demeaned by the society

we live in, unloved by those we depend on, alienated amidst technical processes

which make us seem small and useless, repressed by stifling routines arising

from machines and business, and cowardly to live as we do with bowed souls, we

will become immune to the temptation of the heroism of violence and the thrill

of 'blowing it all up.' The

militarized 'holiday' from nothingness - rushing towards the freedom of illusory

causes and redemptions dripping with blood - will no longer be necessary.

We will, instead, become the loving creators of a new world, focused on

the art of life, and be dutiful in preserving it.

We will face rightful challenges that raise us instead of staining us;

and for our hearts and souls to worship, we will build cathedrals of light

rather than cathedrals of darkness.

Our technological genius will cease 'going out at night' like a vampire hungry

for blood, and instead, lead us by the hand through bright, transparent days of

fruitful work and constantly growing selves.

In all of my major works - THE JOURNEY OF RAINSNOW, THE MESSAGE OF RAINSNOW, and

THE MARCH OF THE ECCENTRICS - you will find this thought, this search for a

marriage between Man and the NEW CULTURE that will be his ally instead of his

oppressor, his perfect vehicle for traveling towards peace, justice, and

fulfillment, rather than the jail which stunts him and embitters him, thus

giving birth to a twisted world. In

this way - with this subconscious, ever-present agenda at the helm of all I do -

even my most fantastic escapes from reality are actually a way back to

usefulness... and a plunge into the depths of activism...

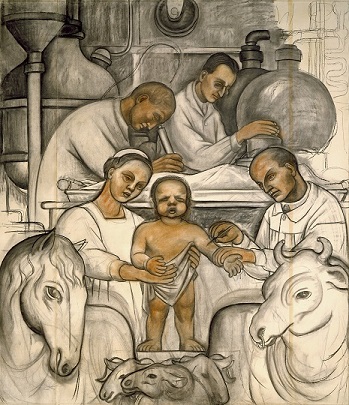

"Vaccination" by Diego Rivera (for the Detroit Industry Mural, 1932), shows the

positive side of technology, properly used by compassionate human beings to

bring hope and health to the world.

PRESIDENT OBAMA'S HIROSHIMA SPEECH

On May 27, 2016, President

Obama visited Hiroshima, the site of the 1945 atomic bombing, in a complicated

political move that infuriated some, under-impressed others, and was shrewdly

studied and analyzed by still others.

Before I get to the text of the speech he made there - an important

statement on the human race's relationship to technology in general, but to

nuclear technology in particular - it is helpful to fill in the context of the

visit.

Before President Obama, no

active US President had ever gone to the site of our most dreadful act of

destruction. Although the US

political establishment had traditionally defended the decision to drop atom

bombs on Japan as a 'justifiable effort to hasten the end of WW 2 and save

American lives', there was a deep sense of discomfort about the use of these

cataclysmic weapons of mass destruction and the horrifying results they had had

on a helpless civilian population.

No US president wanted to step into that geography of guilt, to face the

"hibakusha" ('explosion-affected people' or atom-bomb survivors), their

families, rememberers, and sympathizers; to set foot in that torturous

landscape, rebuilt and life-filled again, but with indignation and moral

incomprehension still in the air, unspeakable memories stuck in the ground.

How could you, as the representative of the nation which had unleashed

atomic weaponry on the world in August of 1945, go to such a place without

weeping tears of shame and begging for forgiveness?

Without 'surrendering' the power of the myth of being right, and bowing

down with the admission that you had been wrong?

At the same time, how could you get away with apologizing to the Japanese

people, without at the same time offending American veterans' groups and many

others, who blamed Japan for starting the war in the first place, and had no

wish to see America's glory tarnished by the confession of a sin, and the good

feeling of an honest victory stained by a crime?

As stubbornly as Japan, for many years, resisted making an official

apology to Korea for the sexual enslavement of young Korean women during WW II

- (these women, designated as 'comfort girls', were rounded up to serve

soldiers in the Imperial Japanese Army) -

so the US would admit no wrong when it came to Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Before going on, let me make

my own view on the matter clear:

yes, Japan started WW II in the Pacific, although its aggressive actions were

actually the result of historical processes set into motion by previous acts of

European colonialism in Asia, which sent it down the road of imperialism as a

means of survival in a cutthroat global environment.

Although Japan, itself, committed numerous atrocities during the war -

from its brutal treatment of the Chinese, epitomized by the 'Rape of Nanking',

to its horrendous treatment of POWs - the worst of its military

transgressors/war-criminals, and the civilians left behind in places such as

Hiroshima and Nagasaki, were not one and the same.

It was wrong to treat them as the same.

Japan was cornered at the time of the bombings, its capacity for

offensive operations beaten down and controllable.

There was time and space to demonstrate the power of the new weapons

without involving live civilian guinea-pigs in the experiment.

The US did NOT have to drop the bombs; in the deepest core of its

decision to do so, was incredible impatience, and quite possibly a desire for

revenge tinged with racism, as well as a wish to impress the Soviet Union as the

first move of the impending Cold War.

I am sorry for whoever this view might offend, but it is my strong

opinion.

In our own time, right now,

many of these political dynamics (guilt and avoidance, and the desire not to

scratch the myth of our goodness) remain nearly as powerful as they were in the

first decades after the war. Conservative

Americans were not about to endorse Obama's trip to Hiroshima (they felt it

would be a stomach punch to patriotism), while China was against the trip, not

wishing Obama to go to a place which would automatically trigger emotions of

sympathy for Japan and show it as a 'victim', rather than as a 'perpetrator' who

should be eternally distrusted. They

were also afraid the trip could signal a subtle shift in US Far-Eastern Policy,

and the beginning of an effort to replace China as America's main go-to

nation in Asia (the nation we have to work with on all matters of importance), with Japan; at the very least, they feared a U.S. effort to cultivate Japan as a

powerful counterbalance to Chinese ambitions in Asia.

Neither conservative Americans nor the Chinese would support an American

'apology' for the bombing of Hiroshima.

Yet how could President Obama go there (as he sought to strengthen

America's bond with Japan) without doing so?

In the end, our President did

what most politicians do under such circumstances.

He steered a middle course, pleasing no one, yet establishing a moral

beach head for the future. Although

he did not feel secure enough to make an apology for the atomic bombings, the

very fact that he went to Hiroshima and provided gestures of sympathy for the

dead, was a huge improvement over the utter avoidance of the past.

His speech contained strong elements of compassion in it, yet at the same

time escaped from the searing subject of Hiroshima, itself, by mainly using

Hiroshima as a springboard to deliver thoughts on the historical and

philosophical challenges of harnessing our technological prowess, as a species,

for constructive, worthy and humane goals, rather than allowing it to be

kidnapped by our darker impulses and used to destroy.

In this way, but somewhat softly, he put in a word for nuclear

disarmament (proposing it as a long-term human goal, but relegating it to an

indefinite future).

I am posting the text of the

speech created by Team Obama as the centerpiece for the President's Hiroshima

visit, because I think it is an eloquent speech with a lot of well-spoken

passages and flashes of brilliance. But

the material isn't at all new. Years

ago Einstein is reputed to have said:

"[If there is a Third World War] the Fourth World War will be fought with

rocks." He and many others involved with

the creation of the atom bomb, including Oppenheimer and Fermi, had come to

fully grasp the idea that Man's technological abilities had brought Him to the

brink of self-destruction, and that our moral development was lagging

dangerously behind our technological development, seemingly advancing at a far

slower rate. If the gap between the

two forms of development were not somehow quickly closed, the inevitable result

would be that we would one day be run over by powers we did not have the wisdom

to control. The so-called Fermi

Paradox, one of the clearest statements of this concept, even wielded it as a

possible explanation for why we have not yet been contacted by extraterrestrial

civilizations (if that is, in fact, true), surmising that the large number of

intergalactic civilizations predicted by the Drake Equation may have been offset

by a tendency of developing civilizations to destroy themselves before they are

able to attain the ability of advanced space travel.

These ideas later became popularized in such books as WE ARE NOT ALONE by

Walter Sullivan and EXTRATERRESTRIAL CIVILIZATIONS by Isaac Asimov.

I used them in my own sci-fi works, as have many others, and also made

such concerns principal ones for Julius Abu in my MARCH OF THE ECCENTRICS novel.

(To just throw in one more idea:

I believe that self-knowledge, together with culture as a vehicle for

channeling our 'human nature' towards its best options, are our only hope for

survival. Our 'biology' will not

'catch up' with our technology, in the sense of being to overtake it with a true

sense of responsibility before we succumb, unless it is properly understood, and

then filtered and directed through a carefully-crafted, and significantly

redesigned culture.)

What is particularly important

about President Obama's speech on technology and the human future, in addition

to its undeniable eloquence, is the fact that it was delivered by a major

political leader (not just a sci-fi writer or a brilliant scientist in the

throes of remorse), and that it was given at a location of supreme symbolic

significance. From the deepest hole

of Mankind's failings, words of our highest aspirations were pronounced.

That has value. What will

have even more value will be the day when men of power, and the forces that

impel and constrain them, have finally reached the point where they are able to

step away from their damning pride, and from the high-sounding words that

barricade them behind that pride, and to say what should be obvious to any

heart: that human life is precious,

and that that one concept (let it be a feeling) should be the basis of our

civilization and the birthplace of all our future history.

On the day it is no longer hard to apologize for Hiroshima... on the day

when that apology comes easily, naturally... on the day it won't let itself be

held back by anything, but just comes running out of us with genuine emotion,

unstoppable... on that day, we will have taken the first true step towards the

salvation of our planet.

(NOTE:

The text of the speech below, is provided by THE NEW YORK TIMES.)

THE PRESIDENT'S SPEECH:

Seventy-one years ago, on a

bright cloudless morning, death fell from the sky and the world was changed. A

flash of light and a wall of fire destroyed a city and demonstrated that mankind

possessed the means to destroy itself.

Why do we come to this place,

to Hiroshima? We come to ponder a terrible force unleashed in a not-so-distant

past. We come to mourn the dead, including over 100,000 Japanese men, women and

children, thousands of Koreans, a dozen Americans held prisoner.

Their souls speak to us. They

ask us to look inward, to take stock of who we are and what we might become.

It is not the fact of war that

sets Hiroshima apart. Artifacts tell us that violent conflict appeared with the

very first man. Our early ancestors having learned to make blades from flint and

spears from wood used these tools not just for hunting but against their own

kind. On every continent, the history of civilization is filled with war,

whether driven by scarcity of grain or hunger for gold, compelled by nationalist

fervor or religious zeal. Empires have risen and fallen. Peoples have been

subjugated and liberated. And at each juncture, innocents have suffered, a

countless toll, their names forgotten by time.

The world war that reached its

brutal end in Hiroshima and Nagasaki was fought among the wealthiest and most

powerful of nations. Their civilizations had given the world great cities and

magnificent art. Their thinkers had advanced ideas of justice and harmony and

truth. And yet the war grew out of the same base instinct for domination or

conquest that had caused conflicts among the simplest tribes, an old pattern

amplified by new capabilities and without new constraints.

In the span of a few years,

some 60 million people would die. Men, women, children, no different than us.

Shot, beaten, marched, bombed, jailed, starved, gassed to death. There are many

sites around the world that chronicle this war, memorials that tell stories of

courage and heroism, graves and empty camps that echo of unspeakable depravity.

Yet in the image of a mushroom

cloud that rose into these skies, we are most starkly reminded of humanity’s

core contradiction. How the very spark that marks us as a species, our thoughts,

our imagination, our language, our toolmaking, our ability to set ourselves

apart from nature and bend it to our will — those very things also give us the

capacity for unmatched destruction.

How often does material

advancement or social innovation blind us to this truth? How easily we learn to

justify violence in the name of some higher cause.

Every great religion promises

a pathway to love and peace and righteousness, and yet no religion has been

spared from believers who have claimed their faith as a license to kill.

Nations arise telling a story

that binds people together in sacrifice and cooperation, allowing for remarkable

feats. But those same stories have so often been used to oppress and dehumanize

those who are different.

Science allows us to

communicate across the seas and fly above the clouds, to cure disease and

understand the cosmos, but those same discoveries can be turned into ever more

efficient killing machines.

The wars of the modern age

teach us this truth. Hiroshima teaches this truth. Technological progress

without an equivalent progress in human institutions can doom us. The scientific

revolution that led to the splitting of an atom requires a moral revolution as

well.

That is why we come to this

place. We stand here in the middle of this city and force ourselves to imagine

the moment the bomb fell. We force ourselves to feel the dread of children

confused by what they see. We listen to a silent cry. We remember all the

innocents killed across the arc of that terrible war and the wars that came

before and the wars that would follow.

Mere words cannot give voice

to such suffering. But we have a shared responsibility to look directly into the

eye of history and ask what we must do differently to curb such suffering again.

Some day, the voices of the

hibakusha will no longer be with us to bear witness. But the memory of the

morning of Aug. 6, 1945, must never fade. That memory allows us to fight

complacency. It fuels our moral imagination. It allows us to change.

And since that fateful day, we

have made choices that give us hope. The United States and Japan have forged not

only an alliance but a friendship that has won far more for our people than we

could ever claim through war. The nations of Europe built a union that replaced

battlefields with bonds of commerce and democracy. Oppressed people and nations

won liberation. An international community established institutions and treaties

that work to avoid war and aspire to restrict and roll back and ultimately

eliminate the existence of nuclear weapons.

Still, every act of aggression

between nations, every act of terror and corruption and cruelty and oppression

that we see around the world shows our work is never done. We may not be able to

eliminate man’s capacity to do evil, so nations and the alliances that we form

must possess the means to defend ourselves. But among those nations like my own

that hold nuclear stockpiles, we must have the courage to escape the logic of

fear and pursue a world without them.

We may not realize this goal

in my lifetime, but persistent effort can roll back the possibility of

catastrophe. We can chart a course that leads to the destruction of these

stockpiles. We can stop the spread to new nations and secure deadly materials

from fanatics.

And yet that is not enough.

For we see around the world today how even the crudest rifles and barrel bombs

can serve up violence on a terrible scale. We must change our mind-set about war

itself. To prevent conflict through diplomacy and strive to end conflicts after

they’ve begun. To see our growing interdependence as a cause for peaceful

cooperation and not violent competition. To define our nations not by our

capacity to destroy but by what we build. And perhaps, above all, we must

reimagine our connection to one another as members of one human race.

For this, too, is what makes

our species unique. We’re not bound by genetic code to repeat the mistakes of

the past. We can learn. We can choose. We can tell our children a different

story, one that describes a common humanity, one that makes war less likely and

cruelty less easily accepted.

We see these stories in the

hibakusha. The woman who forgave a pilot who flew the plane that dropped the

atomic bomb because she recognized that what she really hated was war itself.

The man who sought out families of Americans killed here because he believed

their loss was equal to his own.

My own nation’s story began

with simple words: All men are created equal and endowed by our creator with

certain unalienable rights including life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

Realizing that ideal has never been easy, even within our own borders, even

among our own citizens. But staying true to that story is worth the effort. It

is an ideal to be strived for, an ideal that extends across continents and

across oceans. The irreducible worth of every person, the insistence that every

life is precious, the radical and necessary notion that we are part of a single

human family — that is the story that we all must tell.

That is why we come to

Hiroshima. So that we might think of people we love. The first smile from our

children in the morning. The gentle touch from a spouse over the kitchen table.

The comforting embrace of a parent. We can think of those things and know that

those same precious moments took place here, 71 years ago.

Those who died, they are like

us. Ordinary people understand this, I think. They do not want more war. They

would rather that the wonders of science be focused on improving life and not

eliminating it. When the choices made by nations, when the choices made by

leaders, reflect this simple wisdom, then the lesson of Hiroshima is done.

The world was forever changed

here, but today the children of this city will go through their day in peace.

What a precious thing that is. It is worth protecting, and then extending to

every child. That is a future we can choose, a future in which Hiroshima and

Nagasaki are known not as the dawn of atomic warfare but as the start of our own

moral awakening.